--Greg Armstrong -- Last updated April 19, 2023

A Results Approach to Developing the Implementation Plan: A Guide for CIDA Partners and Implementing Agencies

Download it before it disappears. Peter Bracegirdle’s Guide to developing the Project Implementation Plan is a logical, carefully structured tool for planning large projects. It can be useful, not just for people working on CIDA projects but for anyone trying to put together the pieces of a complex project or programme.

|

| Cover page of the old CIDA PIP Guide |

Level of difficulty: Moderate

Primarily useful for: Planning large projects

Length: 98 pages

Most useful sections: Examples illustrating how each component of project planning works.

Minor Limitations: Some CIDA-specific RBM jargon and it takes considerable time to actually work through these processes in real life.

CIDA’s user-friendly former comprehensive project planning Guide

This document was nine years old when I first reviewed it in 2010, and although some of the terminology in it has been superseded by new RBM terms the Canadian aid agency CIDA adopted in 2009, this is still one of the most useful guides to planning large projects - for any donor - currently available. While a lot of other RBM guides from large organizations come across a bureaucratic and boring, Peter Bracegirdle's writing, presentation and illustrations make this a much more accessible, user-friendly guide than any others I have come across.

But, it is just barely available. It is no longer directly downloadable from the CIDA (now GAC) web site, and it is not available even from sites such as the Monitoring and Evaluation News, which have most, even “out of print” donor documents. A Google exact word search for the Guide in 2022 returns 242 hits, many bibliographic references by other donors, providing a link to a CIDA site, that itself has expired. In theory you might once have been able to get a copy from CIDA by sending an email to CIDA’s Performance Management Division but but that is no longer possible.

I have an old PDF copy of this guide, and a couple of hard copies, and you can still get it from several sites including Businessdocbox, but if all else fails, here is an archived copy.

CIDA changed into first DFATD and then Global Affairs Canada under different governments, has been, and continues to work on revamping its results-based management terms and guides, and the document was removed from the CIDA/DFATD/GAC website pending adaptation to the new terminology. I would not count on the PIP guide (PIP for Project Implementation Plan), as it is known, ever being reintroduced. And, although there are some useful new RBM guides being produced by Global Affairs Canada, this old PIP guide is easier to read than many subsequent guides, and worth looking for because it gets down into the dirty details of how we can plan in practical terms for a project - not just for the Canadian aid agency, but for any organization.

Who this Guide is for

This is not a guide I would suggest for small projects. It is long and will take time to work through, time that may not be a good investment if a project is short-term or low-cost. But for anybody starting out on the planning process for a longer (2 years or more) complex, or expensive project, regardless of who is funding it, this guide can help put the sometimes daunting process of building and then fielding a complex project into a usable, coherent framework.

I know of one international lawyer who has seen this document for the first time and is happily using it in April 2023 for the design of a rule of law project.

While the guide has some CIDA-specific jargon, the logical and (everything is relative) user-friendly structure of the guide can help produce a functional, and understandable plan for most large projects. I know several project managers who refer to it still, as a guide to sorting out their work plans and reports.

This was one of the most important of a series of documents on results-based management produced by and for CIDA roughly ten years ago. The people most likely to benefit from using the PIP guide, therefore, were obviously those working with CIDA projects. Some of the terms are now dated. Global Affairs Canada has changed from the pure Logical framework approach (the LFA), for example, now calls its results “immediate, intermediate and ultimate Outcomes”, uses a logic model instead of a results chain, and has a more complex risk identification process. But the logic in this original PIP Guide is still sound and could easily be adapted to current terms used by Global Affairs Canada or, for that matter, to the work of other agencies.

This guide has considerable potential utility for anybody trying to turn a general project design into a functioning on-the-ground project, for people who want to, or have to, burrow down into the details of planning. It is a tool that should be used with a group, or in multiple sessions, with key project implementation staff, partners and for some components, with stakeholders.

I avoided using this guide for the first several years after it was published, simply because it was so long (97 pages), and, I assumed, too complex for the projects I was working on. That is still true where the projects are under $500,000, but for large projects I was wrong.

When I did use it in a planning workshop on a justice project with a UN agency that was not required to use the CIDA format, we found that while working through the process took considerable time, it was not really intellectually difficult. The Guide helped focus discussions, and tease out the logical implications of how we were putting the project together. I have since used it on two other projects, including governance and environment projects and I regret not using it earlier.

This is not an Results Based Management guide by itself. It assumes that readers have at least an introduction to RBM. But it takes the logical elements of RBM -- problem, results, resources and activities -- and ties them together in a usable format, with easy to understand illustrations and examples.

Each of the 22 units, in six categories, is covered in a two or three pages, including one or two paragraphs on key concepts, a list of clear questions to focus group work, and a practical example of how the questions and framework can be applied in a project.

There are, in total, 111 questions that can be used to focus discussion. The first three units are specific to the CIDA project implementation plan process in particular, but there are, in the remaining 18 sections, probably at least 80 or 90 questions that could usefully be examined for any project.

This is not deep, not revolutionary, but it focuses attention on what we need to know if we are planning a project likely to have any practical impact,and what we need to do if in light of changing circumstances, we need to revise the project design.

This guide assumes the basic project design (the conceptualization of the general need and direction) has been completed, and that now the reader is tasked with doing something to bring ideas into implementation.

On a larger project ($10 million over 5 years) with multiple partners, three weeks of work was not sufficient to cover all of the territory, but the basic structure of the project, implementable --although requiring much follow-up -- was in place after going through the process. For a project of that size, another two months of serious concerted attention would be needed to get baseline data for the indicators, and through this process eliminate the impractical indicators.

Many donors and implementing agencies do not encourage “long” planning periods, but this is ultimately short-sighted. A reluctance to spending time and money on rigorous planning just means double the time later on monitoring and remedial design.

In CIDA’s projects, and unhappily in the successor agencies DFATD and GAC, for example, while a project implementation planning “mission” to the field before project implementation might be scheduled for a month, it can often take up to a year (or more) for the actual plan to be approved. This is because, in large part, insufficient time and money is often budgeted or spent at the beginning, examining the logic of the project, the way the logic relates to operation, and, at its most basic, focusing on collection of baseline data.

When it later becomes clear that indicators have not been tested, and the logic of the management structure of funding arrangements is vague or confusing, budget and programming delays, and endless rewrites of the plan often are the result.

It does not seem unreasonable to me that for $2 million, a month or two should be spent on serious planning, and two or three weeks each year on reporting. And for $10 million or more, three or four months of serious attention at the beginning, and a month a year later for internal monitoring, can save months of wasted time and perhaps millions of dollars on unfocused activities. OK, it may cost $200,000 to put together a competent plan for a $10 million project, but what is that -- 2% of the total project cost, to focus the effective spending, and reporting on the other 98%?

There are in some cases, examples of projects costing well over $50 million, where no clear attempt to examine the logic was ever undertaken, until critical evaluations raised the uncomfortable questions that should have been asked many years, and many millions of dollars before.

For consultants who do both planning and monitoring, donors skimping on planning should not be a problem -- because they will get the work later, anyway, as donors and executing agencies scramble to retrieve the mess created by the rush to implementation.

The first three chapters introduce where the Project Implementation Plan is in the CIDA structure, and those not working with CIDA can probably safely skim these.

The other major sections of the guide include units, with key questions and examples on

Limitations: This is a summary of basic processes. It does not explore any of these ideas in detail, and genuinely working through these issues will take considerable time, and the participation of all of the stakeholders, something the author emphasizes.

The bottom line: This guide won’t do the work for you, and it won’t implement the project, but it will help you define a rational structure for a large or complex development project. You may decide to use only part of it, but there is a real logic to the sequence here. Taking each part seriously and working it through, does, it turns out, make sense.

_____________________________________________________________While the guide has some CIDA-specific jargon, the logical and (everything is relative) user-friendly structure of the guide can help produce a functional, and understandable plan for most large projects. I know several project managers who refer to it still, as a guide to sorting out their work plans and reports.

This was one of the most important of a series of documents on results-based management produced by and for CIDA roughly ten years ago. The people most likely to benefit from using the PIP guide, therefore, were obviously those working with CIDA projects. Some of the terms are now dated. Global Affairs Canada has changed from the pure Logical framework approach (the LFA), for example, now calls its results “immediate, intermediate and ultimate Outcomes”, uses a logic model instead of a results chain, and has a more complex risk identification process. But the logic in this original PIP Guide is still sound and could easily be adapted to current terms used by Global Affairs Canada or, for that matter, to the work of other agencies.

This guide has considerable potential utility for anybody trying to turn a general project design into a functioning on-the-ground project, for people who want to, or have to, burrow down into the details of planning. It is a tool that should be used with a group, or in multiple sessions, with key project implementation staff, partners and for some components, with stakeholders.

I avoided using this guide for the first several years after it was published, simply because it was so long (97 pages), and, I assumed, too complex for the projects I was working on. That is still true where the projects are under $500,000, but for large projects I was wrong.

When I did use it in a planning workshop on a justice project with a UN agency that was not required to use the CIDA format, we found that while working through the process took considerable time, it was not really intellectually difficult. The Guide helped focus discussions, and tease out the logical implications of how we were putting the project together. I have since used it on two other projects, including governance and environment projects and I regret not using it earlier.

Format: Quick Notes on Project Planning

|

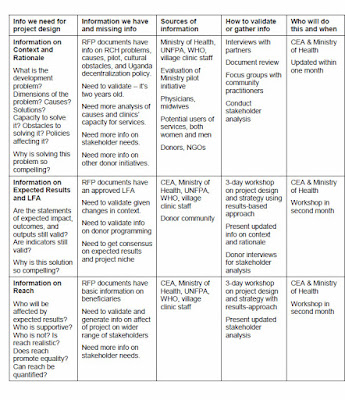

| Organizing tasks for developing the Implementation Plan (click to enlarge) |

Each of the 22 units, in six categories, is covered in a two or three pages, including one or two paragraphs on key concepts, a list of clear questions to focus group work, and a practical example of how the questions and framework can be applied in a project.

There are, in total, 111 questions that can be used to focus discussion. The first three units are specific to the CIDA project implementation plan process in particular, but there are, in the remaining 18 sections, probably at least 80 or 90 questions that could usefully be examined for any project.

This is not deep, not revolutionary, but it focuses attention on what we need to know if we are planning a project likely to have any practical impact,and what we need to do if in light of changing circumstances, we need to revise the project design.

|

| Framework for revising the project design (click to enlarge) |

This guide assumes the basic project design (the conceptualization of the general need and direction) has been completed, and that now the reader is tasked with doing something to bring ideas into implementation.

How Long will it take to use it?

My experience has been that with a relatively small group of people -- ten key staff planning a two-year, single-country project, worth about $2 million -- at least a week is required to work through, in a very cursory manner, the issues outlined here. That built the foundation for the project, but much more work still had to be done to nail down the baseline data, and flesh out the details of the operational and reporting tasks. A project of that size would probably require, therefore, at least a month of full time work to do this properly. Unit 5 of this guide, for example, has ten key questions about the development problem, and examining them carefully with key partners, could easily take two or three days.On a larger project ($10 million over 5 years) with multiple partners, three weeks of work was not sufficient to cover all of the territory, but the basic structure of the project, implementable --although requiring much follow-up -- was in place after going through the process. For a project of that size, another two months of serious concerted attention would be needed to get baseline data for the indicators, and through this process eliminate the impractical indicators.

Resistance to spending money on project planning

In CIDA’s projects, and unhappily in the successor agencies DFATD and GAC, for example, while a project implementation planning “mission” to the field before project implementation might be scheduled for a month, it can often take up to a year (or more) for the actual plan to be approved. This is because, in large part, insufficient time and money is often budgeted or spent at the beginning, examining the logic of the project, the way the logic relates to operation, and, at its most basic, focusing on collection of baseline data.

When it later becomes clear that indicators have not been tested, and the logic of the management structure of funding arrangements is vague or confusing, budget and programming delays, and endless rewrites of the plan often are the result.

It does not seem unreasonable to me that for $2 million, a month or two should be spent on serious planning, and two or three weeks each year on reporting. And for $10 million or more, three or four months of serious attention at the beginning, and a month a year later for internal monitoring, can save months of wasted time and perhaps millions of dollars on unfocused activities. OK, it may cost $200,000 to put together a competent plan for a $10 million project, but what is that -- 2% of the total project cost, to focus the effective spending, and reporting on the other 98%?

There are in some cases, examples of projects costing well over $50 million, where no clear attempt to examine the logic was ever undertaken, until critical evaluations raised the uncomfortable questions that should have been asked many years, and many millions of dollars before.

For consultants who do both planning and monitoring, donors skimping on planning should not be a problem -- because they will get the work later, anyway, as donors and executing agencies scramble to retrieve the mess created by the rush to implementation.

Key Questions for Effective Results-Based Project Planning

The first three chapters introduce where the Project Implementation Plan is in the CIDA structure, and those not working with CIDA can probably safely skim these.

The other major sections of the guide include units, with key questions and examples on

- Assessing information requirements for practical planning.

- Defining the Development Problem.

- Clarifying the logical framework

- Reach and beneficiaries

- Risk analysis

- Incorporating cross-cutting themes, such as gender or the environment

- Sustainability strategies

- Defining a management structure

- Clarifying partner roles and responsibilities

- Specifying oversight processes

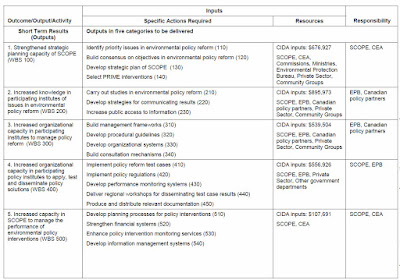

- Relating results to activities and work tasks (the work breakdown structure)

- Using scheduling to focus attention on assumptions behind activities and results

- Relating results to budgets

- Developing internal monitoring, risk management and communication processes.

|

| Output-Activities Matrix (click to enlarge) |

The bottom line: This guide won’t do the work for you, and it won’t implement the project, but it will help you define a rational structure for a large or complex development project. You may decide to use only part of it, but there is a real logic to the sequence here. Taking each part seriously and working it through, does, it turns out, make sense.