Those who have examined or worked with the Results terminology used by U.N. agencies will note difference between this, and the common definition of Outputs used until recently by many U.N. agencies [my emphasis added]:

In practical terms the confusion caused by mixing products and actual changes in capacity into one common category, has meant that only the most serious U.N. agency managers have actually reported on the more difficult changes in capacity.

Their less….ambitious… colleagues have satisfied themselves, although not their bilateral partners, by reporting on completed activities – numbers of people trained, handbooks produced, schools built - as real results.

This has proven to be a real source of frustration to bilateral donors contributing to U.N. agency activities.

Many of these bilateral British, Australian, German, Canadian aid agencies and others, need to report on changes, such as increased skills, better performance, increased learning by students, or improved health, security or income - and not just on activities completed.

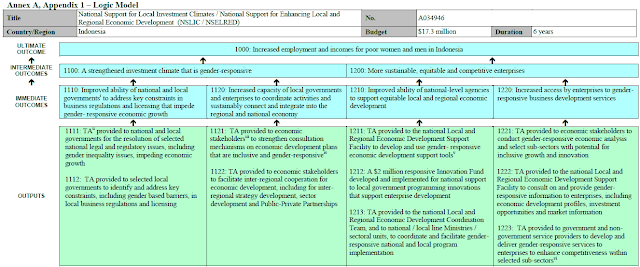

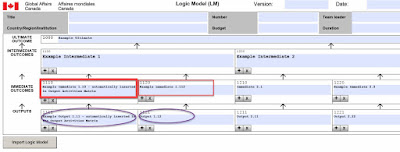

Key GAC RBM Tools: Logic Model, Output-Activities Matrix, Performance Measurement Framework

CIDA in 2008 moved from the familiar Logical Framework, which combined results, indicators, assumptions and risk in a visually (and often intellectually) confusing manner, to disaggregation of the main elements of the Logical Framework into three distinct elements:

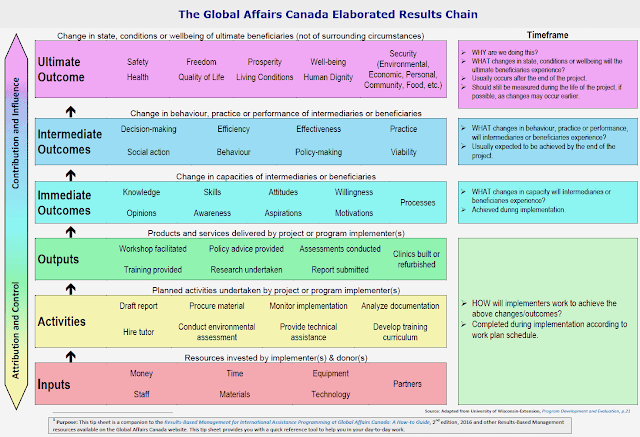

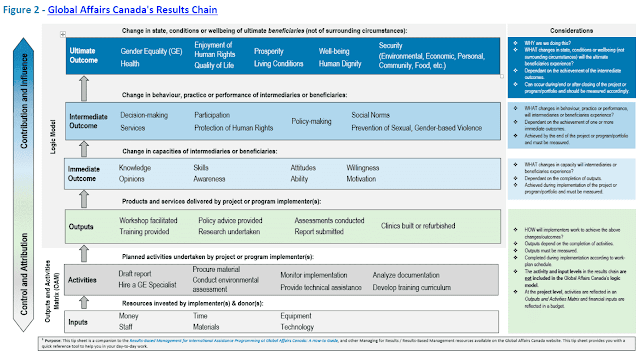

The GAC Logic Model

Based on a theory of change exercise, the Logic Model visually illustrates how different elements are intended to be combined to contribute to short-term, medium-term and long-term changes as this example from a 2015

Request for Proposals (p. 55) for an economic development project in Indonesia illustrates

The GAC Performance Measurement Framework

The Performance Measurement Framework presents indicators, targets data collection methods, frequency of data collection and schedules for different levels of results, as the 2013 example, above, illustrates.

The GAC Risk Management Framework

|

| GAC Risk Assessment Scale |

The GAC Risk Management Framework is a relatively simple combination of tools including a risk assessment scale, risk register, instructions and definitions for 11 primary operational, financial, development and reputational risks.

|

The GAC Risk Framework combination of tools

(click to see details) |

When the tools are used by managers,they are not always updated, however, and some project managers find the process of accurately defining risk difficult.

This more detailed risk assessment tool has 64 questions including rating scales for risk in areas such as procurement, project governance, funding, scheduling, geography, socioeconomic factors, human resources requirements, public perception, communications, project complexity, and integration with other activities, among others.

Not all of these will be relevant to an individual project, but many of these could, and should stimulate some reflection for both those designing projects, and managing them.

RBM templates

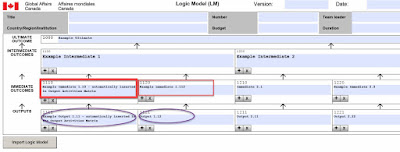

GAC has several templates which, combined could, with some limitations, simplify the mundane if not the intellectual tasks, of distinguishing between and recording the links between Activities, Outputs, and Outcomes in the Logic Model, and in recording agreements on indicators.

The positive side of these templates is that they standardize what is produced, and make it difficult to inadvertently omit or change the wording of results, as we move from a Logic Model to the development of activities and indicators.

|

| Outcome & Outcome statements entered into the GAC Logic Model |

|

| Project Design - Outcome and Outputs from the Logic Model transferred to the Outputs and Activities Matrix (click to enlarge) |

The negative side of these templates – form-filling PDF files, which restrict reformatting, is that they can be difficult to work with if the forms are being projected onto a screen and being used as the basis for discussion in large Logic Model and indicator workshops, where using the suggested “sticky notes” is not practical.

In those situations reformatting is often necessary to accommodate changes as the discussion occurs – as new columns and notes need to be added to remind participants how these changes have evolved, and what needs to be done. In my experience this is not possible with these forms.

This could be handled subsequent to a workshop in additional text, but it is best to get these things on record quickly, while the discussion is taking place. In these situations I have found word processing programmes such as Microsoft Word or Google Docs much easier to work with than PDF or spreadsheet formats.

Another difficulty is that the Logic Model template limits users to 3 Intermediate Outcomes, and in many projects there could be an argument that there will be more, if a theory of change analysis leads to this.

These templates are convenient, therefore, for GAC's own internal management and standardized aggregation of results across hundreds of projects, but they can be restrictive to individual users. And as I will discuss later, GAC has

not done a very good job of actually aggregating results, in any case.

The templates for these tools are not part of the actual GAC RBM Guide itself - at least not as of this writing, and although download links are provided either in the text or at the Global Affairs website, it is not easy, if you are using Chrome, or Microsoft Edge to actually see the templates or download them even if you own Acrobat.

This can be circumvented in Firefox by clicking on the download button and selecting the option to open the file in Adobe Acrobat or Reader, but in Edge and Chrome opening a readable copy or downloading anything beside an error page is very difficult, not just for me, but for many other people I have talked to. However, if you want to give it a shot, there are, theoretically links to the templates for the

Logic Model, the

Performance Measurement Framework, and the

Risk Table - but you may get an error message.

This may be just as well, because while the tools are useful the PDF format is too restrictive to be used easily.

Additional tools for organizing data and reporting results are suggested in the GAC results reporting guide, including separate worksheets to help organize information on Outcome and Output indicators, prior to writing a narrative report, and guidelines on how to put information together in a results report. There are so far no downloadable templates for these, but the formats are easy to copy and use in a standard word processing programme - something I also suggest for the Logic Model, the PMF and risk tools.

Improved operational clarity

All of the basic tools remain essentially the same as they were in 2008, but the improvement over earlier CIDA guides produced after 2008 is that there is increased clarity in this document, and in the Results Reporting Guide, about how to use the Logic Model, Output-Activities Matrix and Performance Measurement Framework, in practical terms in project design, implementation, monitoring and results reporting.

The 2001 PIP Guide remains a useful tool, as it had more detail on some design issues such as the Work Breakdown Structure, activity scheduling, budgeting and stakeholder communication plans. But the new Guide, working with earlier material after 2008, and with new examples, contains useful new clarifications throughout the document.

Distinguishing between Outputs and Activities:

the Output-Activities Matrix

This sounds mundane, but there has been confusion in some Logic Models about whether Outputs were just completed activities or something more. So, in that approach, an activity might be “Build wells” and the Output would be “Wells built”. This is of no use at all in helping project managers mobilize and coordinate the resources and individual activities necessary to really put the wells in the ground.

I have always found the CIDA (2001) Output-Activity Matrix to be a useful bridge between the theory of the Logic Model, and the need for concrete focus in work planning. This document makes this link between the Logic Model and operational reality, and the link to results-based scheduling, clearer.

The current GAC template for the Logic Model automatically populates the Output-Activities Matrix with Outputs, preparatory to the users figuring out what activities are necessary to achieve them.

|

| An example of the Outputs-Activities Matrix after Activities are added |

This form itself provides the foundation for results-based scheduling of project activities as the next logical step in project design, particularly at the stage of project inception.

Results-Based Scheduling Format

Examples of how to phrase Outcomes in specific terms (syntax)

The GAC RBM framework has several criteria for developing precise result - Outcome statements, reflecting the fact that these are supposed to represent changes of some kind for specific people, in a specific location. The RBM guide provides illustrations of two ways this can be done:

|

| Syntax Structure of an Outcome Statement - Global Affairs Canada |

The Guide also provides examples of strong and weak Outcome statements, with suggestions on how they can be improved.

|

| Examples of strong and weak Outcome statements |

A new GAC Results Reporting Format

The RBM How-to Guide and the GAC results reporting guide provide useful new (for GAC projects) formats for results reporting. In the past different projects have reported in a wide variety of ways, often forcing readers to wade through dozens of pages of descriptions of activities, in a vain attempt to find out what the results are.

This new results reporting format puts results up front, in a table, emphasizing indicator data, with room for explanations in text, below.

The results reporting guide also includes separate worksheets to help organize information on Outcome and Output indicators, prior to writing a narrative report and guidelines on how to complete such a narrative report. These are available only as models, not as downloadable templates.

|

Global Affairs Canada Results Reporting Forms (click to enlarge)

|

The main GAC RBM How-To Guide provides other examples of how results should be organized for reporting in table form.

|

| Suggested Results Reporting Format - emphasizing progress against indicators and targets (click to enlarge) |

These and other results reporting tips can be found in section 3 – Step by Step Instructions on results-based project planning and design (p. 66-85) and section 4 – Managing for Results during Implementation (p. 86-92) but others are spread throughout the document, and for that reason it is useful to read the whole document, even if users are familiar with past CIDA/GAC documents. The 2022 revision of the RBM guide contains one additional graphic putting together the steps involved in implementing RBM.

|

| Using indicator data to manage for results - GAC update 2022 |

Limitations of the GAC RBM Guides

I see two areas where further improvements could be made, some of which could be done informally, and some which, given procedures in the Government of Canada's Treasury Board, are perhaps beyond the scope of the GAC RBM group’s control.

1. Dealing with the Implications of RBM for operations and funding

I have seen very small civil society organizations face lengthy processes of data collection and report revisions, to comply with donor agency RBM requirements for relatively inexpensive projects. But at the same time donor agencies themselves - and this means most donors - often do not deal realistically with the implications of their own guidelines for project budgets.

The costs of baseline data

Take baseline data collection, for example. The GAC Guide sections on Indicators and the Performance Measurement Framework (p. 52-64) are generally quite practical, and make the very valid point that baseline data for indicators must be collected before targets can be established, and results reported on.

I agree completely that this is the most useful way to proceed – if the time and budget are allocated to make it possible. As the GAC guide says about baseline data (I have added emphasis):

"When should it be collected?

Baseline data should be collected before project implementation. Ideally, this would be undertaken during project design. However, if this is not possible, baseline data must be collected as part of the inception stage of project implementation in order to ensure that the data collected corresponds to the situation at the start of the project, not later. The inception stage is the period immediately following the signature of the agreement, and before the submission of the Project Implementation Plan (or equivalent). "[p. 60]

In a rational process this would in fact be the situation. But the reality is that for projects funded by GAC and many other donors, after two or three years of project design and approval processes, both the donor and the partners in the field want to start actual operations quickly.

The amount of time allocated by donors and partners for the inception field trips by implementing agencies – and the budget allocated to support baseline data collection processes - are both too limited to make baseline data collection for all indicators during the inception period feasible in all but the most unusual cases.

A typical inception field trip for an inception period might last 3-4 weeks, rarely longer, and during this period

- a theory of change process has to be initiated with all of the major stakeholders,

- an existing logic model tested and perhaps revised,

- a detailed work breakdown structure, and risk framework developed,

- institutional cooperation agreements negotiated, and

- detailed discussions on a Performance Measurement Framework with a multitude of potential stakeholders completed.

As the GAC guide states:

"As with the logic model, the performance measurement framework should be developed and/or assessed in a participatory fashion with the inclusion of local partners, intermediaries, beneficiaries and other stakeholders, and relevant Global Affairs Canada staff." [p. 57]

Some of these indicator discussions alone, where an initial orientation is required, and where there are multiple stakeholders, with different perspectives and different areas of expertise involved, can take 20 or 30 professional staff of a partner agency one or even two weeks in full time sessions, to reach initial agreement on what are sometimes 30 or 40 indicators.

In some cases baseline data are available immediately, and that is one important criterion in choosing between what may be equally valid indicators.

But in many cases, the data collection must be assigned to the partner agencies in the field, who know where the information is, and how to get it. All of this means that a second round of discussions must be undertaken, to discard those indicators for which baseline data are unavailable, or just too difficult to collect and agree on new indicators. And, as the GAC guide quite correctly notes:

"The process of identifying and formulating indicators may lead you to adjust your outcome and output statements. Ensure any changes made to these statements in the performance measurement framework are reflected in the logic model." [p. 81]

The partners, meanwhile, have their existing work to continue with – and rarely see the baseline data collection as their most important operational priority given the political and institutional realities they face, as they do their normal work.

I have participated in several design and inception missions, and I can't remember when baseline data for all indicators were actually collected before the project commenced. At mid-term in many projects it is not unusual for an audit of the indicators by a monitor to find that 30-40% of the indicators may not have baseline data, even after two or three years of project operation.

GAC itself appears to find it difficult to get baseline data for all of its agency-wide indicators, as I will discuss in the conclusion to this article.

All of this could be avoided if more money and more time – up to six months perhaps – were allocated to the inception period, with an emphasis on establishing a workable monitoring and evaluation structure, and actually funding baseline data collection.

That means that when a donor agency emphasizes participatory development of indicators, during an inception period, it should be prepared to provide the resources of time and money necessary to make this practical.

2. Limiting the Logic Model to three levels

The GAC logic model has three results levels - for short-term, medium term and very long term changes. This is about standard for most agencies.

But, of course, only two of these levels are actually operational, and susceptible to direct intervention during the life of the project – Immediate Outcomes in the short term (1-3 years on a 5 year project) and Intermediate Outcomes which should be achieved by the end of the project. The Ultimate Outcome level is the result to which the project, along with a host of other external agencies, including the national government, and other donors, may be contributing.

In real life, a Logic Model which actually reflects the series of interventions, from changes in understanding, which are necessary for a change in attitudes, to changes in decisions or policies and changes in behaviour or professional practice, will go through a minimum of 4 to 5 or even more stages where needs assessments, and training of trainers or researchers lie at the beginning of the process, before we get to field implementation of new policies or innovations.

A logic model approximating the reality of project implementation would look like these examples from the

Institute for Community Health in Massachusetts

I have worked with partners in the field during project design where during the theory of change analysis, up to 8 different levels were identified, with assumptions, interventions and purported cause and effect links between these levels, before ever getting to the ultimate long-term result.

It is impractical, the donors would argue, to have even a 5-level Logic Model – and this would indeed require extra work on indicators.

The Global Affairs RBM guide does give a nod, on page 48, to the idea of “nested logic models” This is something I have worked on with partners, and these can sometimes be more complicated to present and to understand than a 4 or 5-layer Logic Model. If this guide is to be updated in 2022 it would be useful to see a more detailed illustration of how the nested logic models could be used.

Some partners have decided to maintain their own more detailed, multi-level logic models, and present a simplified version to the donors. The whole purpose of these tools, after all, is not primarily for reporting to donors – but to help managers determine what interventions are working, and what changes are needed, before they report.

And that is why the process is called Results-Based Management, and not just results-based reporting.

These partners, when an evaluator, a Minister, or a new donor representative has difficulty seeing how a simple two layer Logic Model can actually attribute results to interventions, have additional tools to use. Having produced a more detailed and informal Logic Model for their own purposes, they can produce the real, multi-level Logic Model and explain the relationships.

Even better, if they have a complete, and perhaps revised Theory of Change, they can explain what the Logic Model summary does not show, about alternative paths towards results, about the assumptions underlying the links between activities and results, and about the risks that have to be dealt with if results are to be achieved.

It is unlikely that any donor will agree to a 4 or 5-level Logic Model, but it would be useful, as this Guide will eventually be revised, to include a section illustrating the process of nesting Logic Models, and if possible in 2021, to link each project's theory of change clearly to the simplistic Logic Models, so the limitations of the Logic Models can be seen clearly.

Is the GAC RBM system adaptive?

The CIDA/GAC approach to predictive planning for bilateral aid projects - specifying results and indicators in advance, and insisting that results are reported against those indicators, has been criticised for being too rigid, and "

old school" for complex environments where problems change, and results may also need to change.

In the Logic Model it is almost impossible to make changes to GAC project Intermediate Outcomes, once a project has been approved. These are the results expected, in theory, to be achieved by project end. For these and Ultimate Outcome changes, the process is ultimately so difficult that in almost all cases it has not been worth pursuing, until now.

For more expensive projects (usually over $10 million) the responsible Cabinet Ministers in both Canada and the partner country must agree to the Intermediate Outcomes, for a project agreement to be concluded. For GAC, it is at this level that the scope of a project is determined - and what resources are required.

If GAC officials think that a change in Intermediate Outcomes will mean a change in scope, and either a decrease in the amount of money justified for a project, or an increase in the resources required then the same level of approval, Ministers or other very senior officials on both sides, must agree also to changes in those Intermediate Outcomes.

For all practical purposes, given the many other pressures at the political level in both countries, that is rarely going to happen.

The use of templates for Logic Models which restricts the number of results layers, and the number of Intermediate Outcomes is convenient for agency managers who must aggregate results across a large number of projects, but this reinforces the argument that the RBM tools are designed less to assist in project management, than they are for senior management's agency-wide standardized reporting.

Operational Flexibility

This does not, however, account for the flexibility in GAC-funded projects at the operational level where projects are actually implemented.

Immediate Outcomes can be changed during implementation, and for less expensive projects, Intermediate Outcomes can be revised to suit needs, because the approval process for projects under $10 million does not require Ministerial approval.

As the GAC RBM guide says of the Logic Model and Performance Measurement Framework:

"They are iterative tools that

can and should be adjusted as required during implementation as part of ongoing management for

results."

Changes can be made to Immediate Outcomes if the reasons are documented and approved during the Annual work planning processes by Project Steering Committees, on which are local GAC officers, the implementing agency and partners, and representatives of the partner government. This is not that difficult to do, if the situation warrants it. =

As I note in the final section of this review, GAC itself has changed its own agency-wide results

And there are other areas in which the GAC results system is more responsive to change than may appear on the surface.

Indicator changes

Indicators define what results mean, and these can be changed if a case is made, and a project steering committee, of mid-level officials in both countries, agree that new indicators are better, more practical, or define changing results more accurately than the original indicators.

Beyond this, in some cases it is evident that evaluations may not be based on the Logic Model or the Indicators originally specified, which means, in effect, that GAC is looking to see how a project evolved, and what results occurred, whether originally specified, or not.

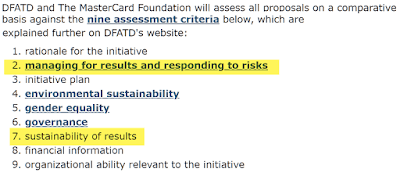

The original GAC call for proposals for organizations to manage the project implied that the GAC RBM standards would apply.

|

| Original GAC Call for Proposals Criteria |

The project design apparently expected that not only would the scholars graduate from public administration programmes, and get work placements for mentoring, but that by the end of the 6 years they would have, in the words of the original Logic Model Intermediate Outcomes "Increased effectiveness [sic]...to contribute to public administration policy development in key sectors..." and "increased effectiveness...to provide leadership" in public administration and policy networks.

While increased knowledge in the field should be possible after degree study, it is unlikely that new leadership qualities would be evident in 5 or 6 years.

Evidently assessing the original project design as unrealistically ambitious, the Terms of Reference for this evaluation state quite clearly that the logic model should not be used as the basis for evaluation, but that, essentially a retrospective theory of change should be constructed.

|

| GAC evaluation criteria - real results vs expected results |

These evaluation Terms of Reference provide more detail [my emphasis, in blue, added]:

"The evaluation must follow the OECD/DAC (2010) Quality Standards for Development Evaluation and best practices in evaluation. Though, references are made to the OECD/DAC criteria (effectiveness, efficiency, relevance and sustainability), the evaluation must not be structured on the basis of the OECD/DAC criteria but rather on the basis of the evaluation questions indicated in section 3.....

Although the implementation of the ... program has been guided by a logic model, it is not appropriate for evaluation purposes. The Consultant must review the intervention logic and construct an explicit causal Theory of Change (ToC). Thus, the analysis of the program’s theory of change, and the participatory update and validation of its intervention logic, will therefore play a central role in the design of the evaluation (inception phase), in the analysis of the data collected throughout its course, in the reporting of findings, and in the development of conclusions and of relevant and practical recommendations."

It appears that the implementing agency did not itself change the Logic Model or the indicators. Had it done so, this would be a positive sign of adaptive results-based management.

It is unclear therefore if this open-ended evaluation was just a hasty move to compensate for problems recognized too late in project implementation to be dealt with by the project implementation team itself amending the theory of change, logic model or indicators - or if it marks a genuine shift to a more adaptive form of RBM by GAC.

But this, combined with the long-standing GAC flexibility on changing results indicators, suggests that there is considerable room for adaptive planning and management in how the RBM tools are implemented, in practice, if managers pay attention to the process.

A Weak Agency-Wide GAC Corporate Results Framework

The current Liberal government was elected in September 2015, and the earliest results framework it could have influenced would have been that for the 2016-17 fiscal year.

In July 2016 the Canadian government issued its

Policy on Results, which among other things mandated the production for every government department of a Departmental Results Framework "that sets out the department’s Core Responsibilities, Departmental Results, and Departmental Result Indicators". That policy made it clear what a Departmental Result should look like:

"Departmental Results represent the changes departments seek to influence. Departmental Results are often outside departments’ immediate control, but they should be influenced by Program-level outcomes."

Notably, that policy did not specify a format which included either a theory of change or a Logic Model, but simply a general narrative. And it did not establish standards for indicators aside from a definition: "A factor or variable that provides a valid and reliable means to measure or describe progress on a Departmental Result."

Ironically, for an agency which requires even small civil society organizations to produce a Logic Model and a workable performance measurement framework, there is no clear public evidence that GAC itself is aggregating results in any coherent way from Intermediate Outcome-level development results - the results which can be expected at the end of a project, or in GAC's case a series of projects worth roughly C $4 billion.

This is a change from past practice. CIDA, when it was an independent aid agency in 2006 developed a coherent agenda for Aid Effectiveness.

|

| The CIDA Agency Aid Effectiveness Agenda framework in 2006 (click to enlarge) |

This was followed by a new Corporate Logic Model in the 2009

CIDA Business Process Roadmap 4.0, archived, fortunately by

ReliefWeb. Global Affairs Canada itself does not make it easy to find old policy documents.

|

| The former CIDA Corporate Logic Model |

A civil society organization bidding on or implementing a project worth $200,000-$300,000 or even much smaller projects, will be expected to produce a logic model, showing the contribution of short-term results to longer term results. But there is no publicly available evidence of any coherent theory of change, or even a logic model for Global Affairs Canada in general, nor specifically for its development programming.

Global Affairs Canada does not have, then, the kind of Corporate Results Framework that agencies such as the

Asian Development Bank, or the

African Development Bank have developed, and some (but not all) UN agencies have, making it clear how project level results relate to country programmes, some wider agency-wide framework, and ultimately to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

The

OECD 2018 Peer Review referenced a developing attempt by GAC to relate project level results to agency-wide results, in an "Architecture for Results of International Assistance". In October 2021 OECD published a short summary of why the

framework, referred to with the acronym ARIA is needed, the complexities of developing it and an illustration of how GAC project results could be related to programme results and agency-wide results.

As of June, 2022, this framework cannot be found among any of the publicly available documents on the GAC website.

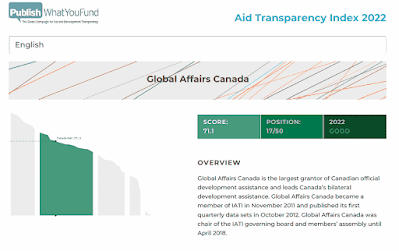

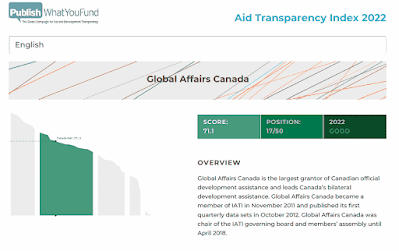

Nor can detailed project results be found online. The

2022 Aid Transparency Index Report, published in August 2022, notes that Global Affairs Canada dropped from a "very good" score in 2021 to "good", with results reporting being the worst component of its score.

|

| GAC ranking on the Aid Transparency Index 2022 |

"The performance component was Global Affairs Canada’s worst component. Results data samples failed; in most cases results were either missing or out of date. We could not find pre-project impact appraisals in Global Affairs Canada’s IATI data or published in other formats. Reviews and evaluations were only partially published"

The report goes on to recommend that GAC

"....should also update and publish actual results data for projects that have been running for several years.

Global Affairs Canada should aim to disclose reviews and evaluations for all relevant activities. "

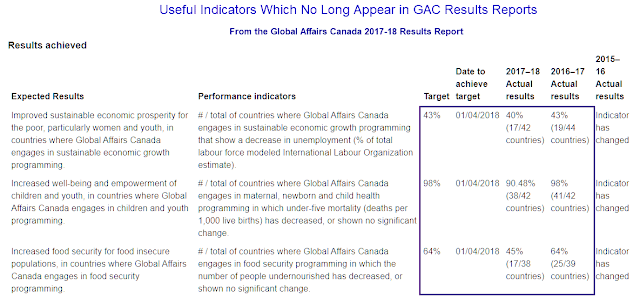

Changing Departmental Indicators

The GAC results reporting page, and the departmental plan do have a list of indicators for each of the 4 areas in which GAC works:

- Diplomacy and Advocacy

- Trade and Investment

- Development, Peace and Security

- Help for Canadians Abroad

- Support for Canada's Presence Abroad

None of these are presented in a manner which demonstrates their contribution to an over-arching long-term result, which GAC itself might call an Ultimate Outcome.

With the exception of Development Peace and Security, where the aid programme is housed, each of the other areas has 3-4 activity or results statements such as

- "Canada's leadership on global issues contributes to a just and inclusive world"

- "Canada helps to build and safeguard an open and inclusive rules-based global trading system"

- "Canadian exporters and innovators are successful in their international business development efforts"

- "Canadians have timely access to information and services that keeps them safer abroad"

- "Personnel are safe, missions are more secure and government and partner assets and information are protected."

The results statements for the development programme are the strongest in GAC's list, actually using the phrasing outlined in the RBM guides:

- "Improved physical, social and economic well-being for the poorest and most vulnerable, particularly for women and girls, in countries where Canada engages."

- "Enhanced empowerment and rights for women and girls in countries where Canada engages"

- "Reduced suffering and increased human dignity in communities experiencing humanitarian crises"

- "Improved peace and security in countries and regions where Canada engages"

- "Canada’s international assistance is made more effective by leveraging diverse partnerships, innovation, and experimentation." (This one would not pass the GAC test, because it combines an activity and a result.)

CIDA, as the development agency was formerly named, in 2011 and 2012 contracted studies on the consistency of Logic Model results and indicators in selected agency priority themes. Those studies, which included only a sample of projects, concluded that while many individual projects had Outputs, Immediate, Intermediate and Ultimate Outcomes consistent with agency priorities, indicator consistency was weak, dealing primarily with Outputs.

Many of the indicators used today for the development results at the agency level - at least as it is publicly presented on the GAC website - are still essentially in

2021 indicators for Outputs, or at best Immediate Outcomes, not indicators for longer term changes. For example (my comments in italics):

- "Number of graduates (m/f) of GAC supported, demand driven, technical and vocational education and training."

- This is perhaps an Immediate Outcome indicator, given that GAC is apparently monitoring the number graduating, but without a Logic Model telling us what activities contributed to capacity development in technical and vocational schools, and improved recruiting of students, it is really difficult to say for sure what this indicator represents. A more interesting indicator of the longer-term effectiveness of the training would be the percent of graduates getting work.

- "Number of women’s organizations and women’s networks advancing women’s rights and gender equality that receive GAC support for programming and/or institutional strengthening." - -

- The question here is - what did they do with the money, and what changes in women's rights or in organizational effectiveness have occurred? As it stands, and in the absence of a Logic Model, this appears to simply be an indicator of an activity - not even an Output.

- It is also distressing to see that this new indicator replaced a meaningful indicator from the GAC 2018-2019 results report: "Percentage of countries that demonstrate an increase or positive change in women’s access and control over property, financial services, inheritance, natural resources and technology.

- That useful indicator was itself new in 2018, but did not survive the year.

- "Number of entrepreneurs, farmers and smallholders (m/f) provided with financial and/or business development services through GAC-funded projects"

- This is essentially an Output indicator. Of more interest would be an indicator related to income, or the sustainability of the farming, after the entrepreneurs and farmers were provided with money and capacity development training.

Occasionally, an indicator does appear which provides more information on the result of activities. For example:

"Percentage of countries that show a decrease in the adolescent fertility rate (number of births/1000 women)."